C2GTalk: An interview with Clara Botto, Co-Founder of Solar Radiation Modification Youth Watch

How can young people take part in Solar Radiation Modification governance?

9 October 2023

How can young people influence United Nations climate talks?

What got you interested in solar radiation modification governance?

What did you learn about marine cloud brightening in Australia?

Why did you set up Solar Radiation Modification Youth Watch (SRM YW)?

What do young people think about solar radiation modification?

How do you see the relationship between solar radiation modification and nature?

How can young people tackle misinformation about climate and solar radiation modification?

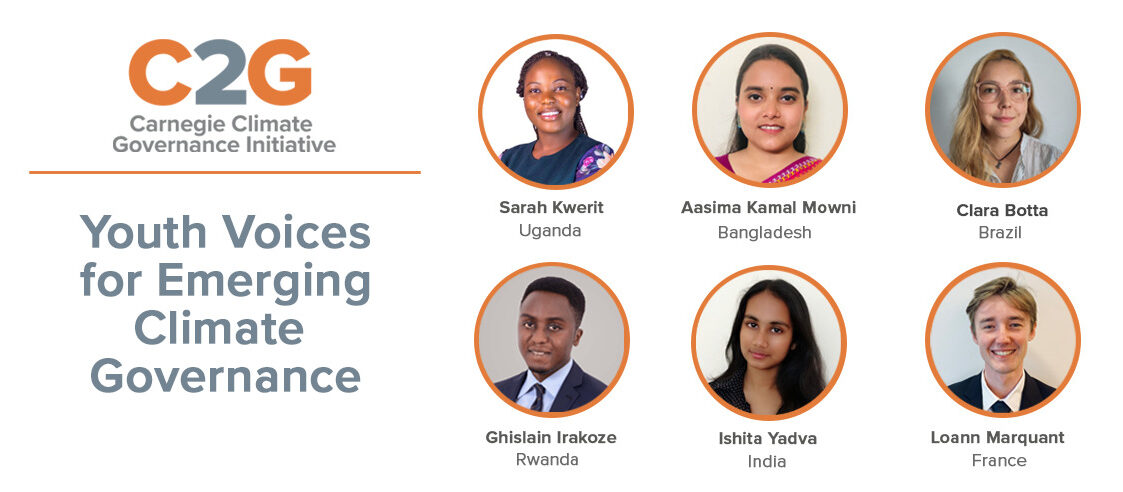

How do you tackle climate anxiety?

Young people need to learn more about solar radiation modification, and provide their inputs to governments, thinktanks, and policymakers, says Brazilian climate activist Clara Botto, in a C2GTalk. “We need to have global conversations to address something that might have global impacts,” she adds. That is why she and colleagues have launched SRM Youth Watch, a global platform aimed at informing and bringing new communities into the debate.

Clara Botto has been engaged with sustainable development at a grassroots and international level, from arts to politics, for the past 8 years. She is currently one of C2G’s Youth Climate Voices developing the platform SRM Youth Watch looking into young people’s perspective of the governance of solar radiation modification, campaigns with World’s Youth for Climate Justice seeking an Advisory Opinion from the International Court of Justice on the climate crisis as a human rights issue, is a New European Voice on Existential Risk with the European Leadership Network and is the Science-Policy Thematic Facilitator of the Major Group on Children and Youth to UNEP.

She holds a MSc in International Development and Public Policy, having written her thesis as a policy case study of deep sea mining in Portugal, and a BSc in Business with focus in Creative Economy and Marketing, where she researched about sustainable fashion and the universities’ lack of preparation to equip youth for sustainable development in Rio de Janeiro.

Specifically on SRM, Clara has also been an observer in the marine cloud brightening fieldwork taking place in the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, participated at the workshop “Managing the Contribution to Global Catastrophic Risk from Climate Change and Solar Radiation Modification” organised by the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk from Cambridge University, joined the Arctic Ice Project’s annual fundraising event in California, and written a statement and science-policy brief for the UN’s 8th STI Forum.

Below are edited highlights from the full C2GTalk interview shown in the video above. Some answers have been edited for brevity and clarity.

Welcome to C2GTalk, a series of one-on-one interviews with influential practitioners and thought leaders to explore the governance challenges raised by emerging approaches to alter the climate.

I am Mark Turner, Senior Communications Consultant with the Carnegie Climate Governance Initiative (C2G), and I am speaking today with Clara Botto, a Brazilian climate justice campaigner who serves as the Science Policy Thematic Facilitator for the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Global Steering Committee of Children and Youth Major Group (CYMG), and is currently working with C2G’s Youth Climate Voices on the governance of solar radiation modification (SRM).

Amongst other SRM-related activities, Clara was an observer to the Marine Cloud Brightening Project fieldwork taking place in the Great Barrier Reef in Australia and wrote a statement and a science policy brief for the UN’s 8th Science, Technology, and Innovation (STI) Forum. Clara also campaigns with World’s Youth for Climate Justice to get an advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice on the climate crisis as a human rights issue, and has been named a New European Voice on existential risk for the European Leadership Network.

Clara Botto, welcome to C2GTalk.

Thank you, Mark. It is great to be here.

Let’s start with your journey. Growing up in Brazil what motivated you to get involved in work on climate change, how do you see the climate crisis affecting your country, and how do you envisage this changing over your lifetime?

Growing up as a kid I was very much connected to nature thanks to my stepfather, who was a bird photographer, so I grew up traveling to random parts of Brazil that my friends were not aware of, definitely not touristy places. At first, I guess I was not aware of all of the problems that we have concerning the environment, but I already had this deep appreciation for nature.

When I was 15, I think that was when I first considered myself an activist for the environment because of veganism protests. When I was 15, I became vegan and I understood that our current food systems have a huge impact on the climate. That was my entry point into climate work. Then, shortly after that, in different aspects of my life and my studies, I made sure that I was linking what I was doing to both the environment and climate.

Regarding your question on how the climate crisis is impacting Brazil, I think in the different places I grew up in there I was familiar already with natural disasters, which to my view are not “natural” because the disasters themselves only happen because our communities are not resilient to withstand the phenomena. I think we had already been seeing those happening in the past decades, but with the climate crisis, as we all know, they will be intensified. I am really worried because we still do not have cities and communities that are resilient to those events, and the tendency is that they will become more frequent.

In your self-introduction you said that you realize you are a climate activist. What does that mean to you? What does it mean to be an activist?

I think it is standing up for what you believe in and for what you believe is wrong, so it is publicly speaking of the things you believe should be changed; and, in my experience, also pointing out solutions or different pathways to the current narrative or the system that we have.

Then of course you got involved in international climate diplomacy. How did that happen? How did you get involved in the world of the United Nations and climate talks?

I think, like many of my friends at school, we had the typical Model United Nations system being discussed in class, and also being part of Model UN. I was actually part of one Model UN about the World Water Conference, if I am not mistaken, when I was 15 or 16, around then. Later on I became aware that there were opportunities to get involved in the UN system as a young person.

In 2018, I believe you were a youth delegate to the UN Youth Assembly. How did you find that — you had done the Model UN; this was the real thing, right? — so how did it find it looked like in practice?

Back then was the first time I was in the United Nations. Of course as a young person when you go there it feels really important. I went with the Brazilian delegation, but the Youth Assembly is not meant to come up with any conclusions or decisions or anything. It really struck me that for quite a few years I felt that I was the only one within the bubble that I was in Brazil who was really concerned about the problems of the world that we face and that wanted to make things, and then going there and being exposed to young people from all around the world gave me a bit of hope that we had a bigger body of people who were trying to do the same things that I was. It felt hopeful.

You mentioned that the Assembly was not there to take decisions per se, but I am interested in how do you feel in general? To what extent do UN processes hear and take into account the concerns of young people? What kinds of avenues are there to make sure that those concerns and thoughts go into some kind of decision-making processes?

I think there are different avenues that a young person can become part of the system. That does not mean that they are efficient and that young voices are really listened to and taken into account, but we have structures, such as youth constituencies to different UN bodies, and I believe that these are pathways that young people find not only to learn but also to make contributions in the different UN processes that we have

What does it mean to be the Science Policy Thematic Facilitator of the Children and Youth Major Group to the UN Environment Programme? There are a lot of different terms in there. Can you help me understand what it all means?

As I just mentioned, we have this system of youth constituencies. The one that serves UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) is the Children and Youth Major Group, as you said, and basically we as young people as part of this constituency can provide our inputs to the processes that UNEP has already been following.

UNEP, whenever they have to consult with their stakeholders, for example, ask the Children and Youth Major Group if we have any contributions to make to specific documents; or if they are hosting a conference, we usually try to make sure we have young people attending who are part of the constituency, and there they can also pressure policymakers, make statements on behalf of the constituency, and so on.

As a Science Policy Thematic Facilitator, me and my colleague are on this one-year mandate, and we have the freedom to look at different science policy processes that UNEP is following, and we can not only provide our own inputs and lens but also then report back to the bigger constituency on what has been discussed specifically on science policy.

Going closer to what C2G does, there is this idea being touted that there could be an approach called solar radiation modification (SRM), which could be an additional source of reducing climate risk by reflecting some sunlight into space. What got you interested in that topic and what attracted you to C2G’s Youth Voices in Emerging Climate Governance program?

The first time that I heard about SRM (solar radiation modification) was back in 2019 at the Climate Geoengineering International Symposium that happened in Rio de Janeiro, where I was based back then. I attended as an observer. First, what really struck me was that I was the only young person in the room, even though it was a public event, and also that “climate geoengineering” and “SRM” back then were terms that I had never heard of before, even though I was already engaged in sustainable development and climate and environmental groups.

Leaving that conference, I was even a bit afraid that I was again the only young person in the room who listened to all of the things that the scientists had said and a bit alone, that no one else was talking about those technologies. So for years, until I heard of C2G, I had SRM and geoengineering as terms in my head but did not have the chance to explore them.

The first time I heard about C2G was in the beginning of 2022, when they were preparing a talk about the role of science fiction and new emerging climate technologies. I had read a lot of science fiction talking about the topic, and that interested me, and it felt really good to see that there were organizations that were looking into something that had been in my head for a while. That is how I got into C2G and SRM with more energy.

Tell me a little bit about how the experience has been. What have you done? What have been the highlights? What have you learned about SRM and its governance doing this?

I think it was a very enriching experience in the sense that I had the opportunity to take a step back and really learn about not only the science but what various stakeholder groups have been saying about SRM and what is the current state of SRM governance that we have in the world.

I was someone who was already interested in the topic and even a bit scared that those things were not being discussed in a mainstream way. It gave me a lot of knowledge and the chance to engage with people who were already either doing research or had been talking about those things for years.

Let’s maybe dig into some of the actual SRM approaches being explored. The most well-known one that often gets the headlines is this idea of stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI) — we will talk about that in a second — and others including marine cloud brightening and ground albedo modification. Let’s take a couple of these in turn.

I was interested to see that you were an observer to the Marine Cloud Brightening Project in Australia. I would love to hear a bit about that experience, what you did, what impressions you got, and what kinds of issues you think it raises.

I reached out to the team that was doing the marine cloud brightening work in Australia, and I was invited to join them as an observer in the fieldwork. It felt really inspiring to see things that you only read in policy briefs, for example during our learning pathway in C2G, are happening and that there is a big team looking at that and they are really committed to that in the work they are doing.

It is very different reading about different types of technology than actually being there on the scene and seeing how it works. It was definitely an experience. Before I could never imagine what it would look like, and it brought me lots of questions. I already went with questions, and I think I came back with tons more.

Can you describe it a bit? Did you get on the boat? I’m interested in exactly what did you do and what did you see. I would love to hear about what it all looked like in practice.

There are different research stations, and I was mostly in three of them. There were two vessels that were conducting the experiment: one was where the machines were, and the other one was collecting data from the experiment. They also had islands where they were collecting data.

I was mostly in the data vessel and on the island, so I got to spend more time with the scientists who were analyzing the results from the experiment.

What kind of lessons did you come away with about marine cloud brightening and what kind of ideas did this experience give you in terms of how it might need to be governed?

Unlike other SRM technologies, marine cloud brightening is very local. The intention of the experiment in Australia was to protect the Great Barrier Reef from the mass bleaching events that have already been happening in the past years.

The main thing I got from the experiment is that, first, we still need to see if it is viable, if we can get the theory and the lab work of marine cloud brightening into practice. It does not matter if they see that yes, we can brighten the clouds, if there will not be an impact in the Reef.

I believe the process of getting the research done is much bigger than we think because, apart from all of the atmospheric scientists who are looking into that, there is also a huge collaboration that is being done with marine biologists, for example, for them to assess if brightening the clouds can make the Reef more resilient.

You have also expressed interest in learning more about the Arctic Ice Project. Tell us about that and what your initial thoughts are there.

Going to another part of the world, the Arctic Ice Project wants to assess a different type of technology. They use hollow glass microspheres that can reflect solar radiation back. The idea there is that those glass spheres can prevent the glaciers from melting.

They are not doing fieldwork yet. First they need to assess that this technology will not harm the environment — the marine life, for example, under the water where they will place the spheres. I did not attend any of their fieldwork since it is not happening, but I was with their team at a fundraising event to learn more about the current state of research and how civil society as a whole that is supporting their project sees climate intervention.

Let’s move on to stratospheric aerosol injection, this idea of spraying essentially aerosols into the stratosphere to reflect back a small portion of sunlight, perhaps analogous to what happens after a volcanic eruption. What issues does that raise for you and what plans do you have to continue following developments in that area?

I think the key difference, as I mentioned before, is that SAI will involve global impacts, unlike the research done in the Arctic or Australia. Even though I have not personally engaged with any research team that is looking into SAI, only some scattered researchers, I think we need to have global conversations to address something that might have global impacts if we decide that we need to use those technologies.

Under the current global governance system that we have, we do not have solutions for how to govern SAI (stratospheric aerosol injection a form of solar radiation modification). I think as more universities or governments start putting money into SAI research, for example, it is key that we are already putting energy and efforts into talking about its governance.

You and your colleagues from the Youth Climate Voices program are developing a platform, I understand, called SRM Youth Watch. Tell me a little bit about what that will look like, what are your plans with it, and how that can help build governance around these issues?

We are still in the initial stages of coming up with this platform named, as you said, SRM Youth Watch. I think the main idea is that we need to have a global youth platform not only to host youth initiatives that are already looking into SRMs with very different types of technologies and from different areas of studies, from students with a philosophy background that are looking into SRM or engineers looking into that. We want to be a platform that can host those different projects but also hopefully a recognized network that can provide inputs to governments, thinktanks, or even individual policymakers who want to become more informed about SRM.

I am interested in what kind of reactions you have had from fellow climate activists and fellow people in the youth movement to your interest in SRM. Obviously, there are some deep concerns held by many about these approaches, and some would really oppose even research let alone going any further. What kind of reactions have you had, what kind of conversations have you had, and how would you say young people are viewing these ideas?

The main reaction I get is complete shock to hear about these technologies because it is something new. I have been in many situations where climate and environmental activists are just surprised to hear about something that is being discussed in the international sphere but that is not getting their attention. That is one of the reactions that I get.

There is also a bit of the opposite, of not wanting to talk about it because it is in their opinion too controversial.

I have also heard that we should not actually be talking about SRM, not because it is controversial but because we have other priorities, as some of my colleagues think.

And then there are some who are just very skeptical about any climate-altering technologies because they think, It is too sci-fi or not realistic, so why would we waste time talking about them?

Have you ever felt a sense of personal criticism from some people, that, “Oh, you shouldn’t be involved in this?” How have you dealt with that kind of sense that you are taking quite a bold step into this area?

Not criticism about looking into SRM, but I think some young people, because they have never heard of SRM, think it is a bit sketchy, that I am involved with sketchy things or things that only happen behind closed doors, that I am a really futuristic thinker, or something like this.

I would not say that I have received strong negative views toward what I have been doing, but some people are just a bit cautious about where I am coming from and who I am dealing with.

You mentioned earlier your interest in nature and that that is partly what brought you into this. There is one area of concern among some critics that SRM is “unnatural” and that we need to be dealing with these issues not with unnatural things but by going back to nature. How do you feel about the relationship between nature and technology, and how does SRM potentially fit into that?

I think the point that we are at right now is unnatural because we humans have brought us here, so it is already a given. We are in the Anthropocene. We have created all of those things that are happening in the climate around us. In an ideal world I wish we would not be talking about SRM as well, that we would be using only nature-based solutions, for example, to tackle the climate crisis; but then in an ideal world we would not have the climate crisis in the first place.

I think that this strong attachment that I have to nature is actually what brought me into SRM because we need to be looking at all of the solutions that we might have and that might help us to preserve what we have. But I think this also comes with an understanding that we as humans are part of nature because I think ecosystems and nature, if we are speaking of them as being detached from human beings, are much more resilient than we are. So I think it is also bringing us humans back into a position as part of nature and the planet as a whole. 26:03

As you develop this platform which will include sharing information about SRM, what kinds of challenges do you see in a world with so much misinformation right now and with so many confusing sources of experts or non-experts telling everybody all sorts of different things about everything? How do you help young people find the right sources of information to deal with misinformation? How are you going to approach that?

We have to rely on the best science available and trustworthy research that is being done on SRM and inform young people on what those technologies are. I think a lot of misinformation comes from just saying things out of our own mouths and not fact checking, for example.

Also, because again SRM is very controversial and we have very strong opinions about it, I think sometimes people say things that might be wrong just because they have not read an article that was published two weeks ago, for example. This happens because it is a topic that is evolving really fast. I think that information needs to be up to date with the research that has been happening. I think it will be about constantly updating ourselves on what has been going on in the scientific world.

Also, thinking about your work on climate and human rights, do you see a relationship between SRM and human rights and climate justice? How would SRM fit into those frames, those objectives?

I think for communities that are very climate vulnerable historically I think the deployment of SRM in those communities needs to be decided by them as they are the ones who have already been struggling with the climate crisis and who as research tells us will be suffering in the years to come as well.

I think the human rights approach to SRM is that we need to inform communities that will either benefit the most or be negatively impacted the most if we are to use one of these technologies. At this point, I would say it is providing accurate information so that they can make up their own minds about those technologies as well.

Just to finish on this bit about the SRM Youth Watch and your plans on that, is there anything that we should be looking forward to over the coming months, or is it still very much in the design phase?

Last week we had our first event that happened in Bangladesh, and in the coming months, in September, we will be in New York for a side event happening around the UN General Assembly. We have just confirmed that we will be hosting an event on September 17, so save the date, and more information will be published on our website. And then, toward the end of the year we are planning to be part of other environment and global governance-related events.

The website is?

SRMYouthWatch.org.

Maybe I could finish on a broader question about motivation, hope, and anxiety. There is a lot of concern out there about the rising levels of climate anxiety amongst young people and how that might impact the way they see the world and the decisions they make.

How do you maintain hope whilst also being aware of how serious the challenges are and what kinds of advice do you have for others who might be struggling to see a brighter future?

That is a question I get a lot. I do struggle still with climate anxiety, but I have just changed my mind toward how I tackle the climate crisis.

I think I have lived through a phase of “climate doom,” but that did not mean that I was stuck and did not do anything. I think there are stages of climate anxiety that do not really help us move forward or be our best person. If we are just angry and complaining about everything, that will not help because you are not proposing solutions. If you are impacted in a way that just makes you get stuck somewhere, then you are also not moving forward and not progressing.

I think it is not about shutting down the anxiety feelings but it is about how you can use the things that you are feeling to move forward and to help because otherwise we might just end up going down a rabbit hole.

Climate anxiety is a real thing and I know depression can come from climate anxiety. I would say whenever I talk to a friend, for example, who has been struggling, one of the things we can try to is to find where we see ourselves being the most useful in the climate fight, which is not only in climate groups, for example — you can be an artist and contribute; you can be a doctor and contribute — so I think it is just about finding your place and doing the best you can each day.

That is a great thought to end on.

Thank you so much, Clara Botto, for taking part in this C2GTalk.

Thanks, Mark.