Safeguarding biodiversity in carbon dioxide

removal approaches

[The views of guest post authors are their own. C2G does not necessarily endorse the opinions stated in guest posts. We do, however, encourage a constructive conversation involving multiple viewpoints and voices.]

This blog is based on a new paper published in the forthcoming special issue of Global Policy, edited by C2G. To access an early view of the full article, click here.

Carbon dioxide removal (CDR) is garnering increasing attention as part of ‘deep decarbonisation’ pathways to achieve 2°C and 1.5°C temperature limits. However, CDR can also present risks to biodiversity, particularly those techniques that depend on large-scale manipulation of ecosystems and earth-system processes. Biodiversity underpins ecosystem functioning and the provision of all goods and services that are essential to human health and wellbeing.

The potential impacts of CDR activities on biodiversity need to be at the forefront of decision-making around whether to engage in research and the eventual deployment of these techniques.

In 2019 the Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) concluded that biodiversity and ecosystem functions and services are deteriorating worldwide. The IPBES recognised the acceleration of biodiversity loss as a crisis posing risks to humanity and ecosystems on the same scale as climate change. Despite the clear links between ecosystem degradation and climate change, projected IPCC scenarios for limiting warming to well below 2°C and 1.5°C rely on large-scale CDR without serious consideration of any potential threats posed to biodiversity.

“Thinking about CDR interventions in terms of threats to biodiversity offers a starting point to highlight positive options, while cautioning against pursuing options that clearly contribute to known drivers of biodiversity loss.”

Identifying threats to biodiversity

In our paper published in Global Policy, we introduce a threat identification framework to assess the impacts (positive or negative) of various CDR interventions on biodiversity and ecosystems. Thinking about CDR interventions in terms of threats to biodiversity offers a starting point to highlight positive options, while cautioning against pursuing options that clearly contribute to known drivers of biodiversity loss. This can form a basis for targeting research, policy and development efforts.

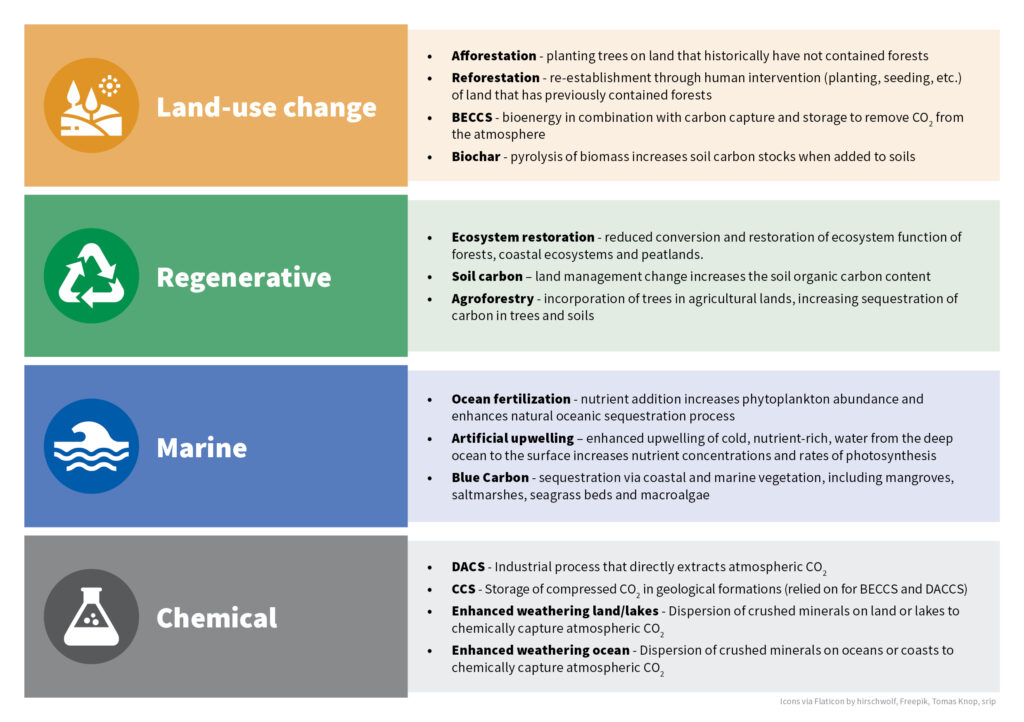

We categorise CDR techniques into four distinct processes: those employing either land-use change, regenerative, marine, or chemical-based processes. For a simplistic assessment of the potential impacts of these CDR techniques, we use the direct drivers of biodiversity loss categorized in the IPBES global assessment as measures for assessing the pressures on biodiversity. This perspective tells us that some types of CDR should be viewed as potentially harmful mitigation interventions, adding to the imperative for rapid and deep decarbonisation to minimise future CDR reliance.

Figure 1: threat identification framework to assess the impacts (positive or negative) of various CDR interventions on biodiversity and ecosystems. Source: Dooley et al. (2020)

Drivers of biodiversity loss

Changes to land and sea use are the leading direct drivers of biodiversity loss. Land-use change is also linked to the other four drivers of biodiversity loss: resource extraction, pollution, invasive species, and climate change itself (with loss of carbon through land-use change).

CDR options requiring land- or sea-use change at any scale (but particularly at the gigatonne scale projected in climate scenarios) will add to already severe pressures on biodiversity. This includes all land-based CDR options that require growing crops or reforesting non-forested land. It also includes macroalgae – expanding seaweed such as kelp forests to sequester carbon.

Marine CDR interventions that are not focused on restoration tend to cause pollution and invasive species, and in the case of ocean fertilisation, resource extraction for mining phosphate-rich rocks.

Chemical CDR interventions in terms of Direct Air Carbon Capture and Storage (DACCS), and enhanced weathering can have negative impacts on resource extraction and pollution through the use of chemical sorbents and the risk of leakage from storage.

Conversely, regenerative CDR options can have an overwhelmingly positive impact on biodiversity, by reversing the direct drivers of biodiversity loss. Options such as enhanced soil carbon, agroforestry, and restoration of terrestrial, freshwater and marine ecosystems do not require land-use change, but restore natural and agricultural systems to optimum functioning and productivity while drawing down atmospheric carbon.

The exception here is the potential impact on climate change where the reversible nature of terrestrial carbon storage presents a risk of failed mitigation. Often called ‘nature-based solutions’ these CDR options come with the risk of reversal if ecosystems are lost – for example, through a wildfire. However, the restoration and ongoing protection of degraded ecosystems improves resilience to external stressors and reduces the risk of reversal.

Governance

Whether CDR contributes to biodiversity loss or enhances biodiversity conservation and protection depends on the specific CDR process. Consideration of the impacts of each CDR technique on biodiversity must be central to CDR governance and decision-making.

In many cases, biodiversity impacts are dependent on the way a particular CDR option is implemented. For example, reforestation could be either negative (if implemented via monoculture plantations increasing invasive species and pollution risks) or positive (if implemented with native mixed species in a manner that buffers and reconnects primary forests). Similarly, enhanced weathering over land could provide positive outcomes if the minerals are drawn from waste stocks rather than freshly mined; if all processing is powered from renewable energy sources; and if the activities are targeted to restore the pH of acidified lakes.

Strong and effective CDR governance frameworks will be critical to maximise the potential for implementation that protects biodiversity.

The IPBES warns that negative trends in biodiversity and ecosystem function are projected to continue or worsen, and that nature-friendly climate adaptation and mitigation will be key to achieving future societal and environmental objectives. Our threat identification exercise suggests that reliance on CDR does not represent a nature-friendly mitigation strategy.

Many CDR options drive the same processes that contribute to climate change and environmental degradation: land-use change and intensive agriculture for bioenergy crops; mining and resource extraction for DACCS; and pollution including greenhouse gases from ocean fertilisation and upwelling.

With the exception of removal options that restore and regenerate nature, CDR should be viewed as an intervention with likely negative impacts on biodiversity loss, adding to the imperative for rapid and deep decarbonisation to minimise future CDR reliance.

Related posts:

Ten opportunities for civil society to shape carbon dioxide removal governance

Guest post by Holly Buck

Carbon Removal: The dangers of mitigation deterrence

Guest post by Duncan McLaren

Tracking corporate plans for carbon dioxide removal

Guest post by Annelise Straw & Wil Burns