C2GTalk: An interview with Per Heggenes, CEO of IKEA Foundation

Why is broad-based governance needed for new climate technologies?

31 October 2022

The world is facing quite a few crises right now — a continued pandemic, food and fuel shortages, rising economic hardship, geopolitical insecurity, and of course a deepening climate crisis. I would like to start with your work at the IKEA Foundation and its support for climate action. Given this challenging context, can you say a little bit about your climate work and what are the values and principles that drive you in your funding decisions?

Absolutely. As you said, Mark, our mission is to create better lives on a livable planet. We look at that as better everyday lives for children and young families living in the Global South basically. That is our focus.

As we worked through the years and learned a lot about what is going on and how we can make a difference, we realized that there are really two big threats faced by people living in the Global South and young people growing up — on one hand, the threat of climate change and, secondly, the threat of poverty — so our grantmaking is focused on those two areas to see how we can make a difference as a foundation in those two specific areas.

The current context, although it is complex and challenging, means that our work with climate action partners becomes more vital and more important than ever before. Climate, energy, food, and health are closely interconnected. You can’t look at them in isolation. People living in lower-income countries are the ones worst affected by these crises, whether it is the climate crisis, global food shortages, and so on.

I think if you look at the global energy crisis, it exposes us to how unsustainable our current systems are and provides an additional motivation and impetus for us to decarbonize our economies and invest in renewables because such an important part of making the world go on is access to energy, but we feel very strongly that the whole transition process will have to be underscored by a level of justice and fairness so that we can ensure a just transition so that there are not winners and losers but all winners. I think we can create everyone into a winner if we do it the right way.

We believe that if we put our minds to doing that, we have to not do it in isolation but collaborate between all the foundations, between governments, businesses, philanthropy, civil society, and the many people to brave these challenges.

What role do you see philanthropy specifically playing in addressing the climate crisis, and how do you as part of the philanthropic sector fit in with the wider ecosystem of governments, businesses, and civil society? What are the mechanisms you use to work together and come to some common action?

What drives me and makes me get up every morning is the fact that we have less than ten years to cut our emissions in half — by 2030 — and there is a very small window left to save the planet. Well, the planet doesn’t need to be saved, but we need to actually ensure the planet is livable.

I think philanthropy can play a catalytic role in this. The main thing is that philanthropy has the opportunity to take risks, and philanthropy should take risks. We can take risks without any specific consequences if we do it sustainably and responsibly.

Examples of that would be that we can de-risk investments in the private sector to actually accelerate and scale up investments in the private sector to improve access to energy. We can help create ecosystems that allow business to focus and develop in the way business should. We can invest in developing solutions, new models, and new ways of trying to be more efficient and more effective in how we provide opportunities for people to lift themselves out of poverty, and we can bridge the gaps between markets and policymakers. We can drive collaborations, as I said before. We can set up structures that help people collaborate toward better opportunities.

We did that, for example, back in 2014 when we invested in setting up what later became the We Mean Business Coalition, which focuses on how business can help drive the world toward net zero. This is an example of an unprecedented collaboration between business, governments, and the financial sector. This collaboration ultimately led to the setup of science-based targets, which is, I would say, the key global standard for businesses to demonstrate how they can maximize their impact in reducing climate impacts that they have through their business.

Do you see any challenge inherent in the fact that unelected foundations essentially could dominate to some degree the climate debate and the ecosystem through their funding? By the way, I ask this fully aware that the initiative I work for also faces occasionally similar questions. How does the idea of philanthropy and the amount of potential influence you have fit in with broader democratic practices?

Well, Mark, part of me says that I wish we could dominate this debate because there is no more important debate to be had right now, but I don’t think we can because, as you probably know, somewhere between 2 and 3 percent of global philanthropy money goes toward climate change. That has to increase dramatically if we are going to get to net zero by 2050. We need to recognize that of course what you bring up is a valid concern. Having said that, we have no time to waste. We need to push.

I think what foundations can do is actually give voice to the many, ensuring that it is not only one interest that is driving this, but it is the interests of the many that moves us together toward where we need to go. We need to dramatically increase the contributions that we are making to tackle climate change from 2 to 3 percent to much more than that.

I think as a foundation we can act to get a better foundation as a checks-and-balances system to make sure we all bring our different values and principles to the party and we agree on a solution that works for everyone. Of course, we need to provide full transparency and need to be held accountable, but in my view we as a foundation have an ulterior motive here; we only have a motive that is a secure and livable planet for the next generations.

How do you measure success, thinking about short-term versus long-term results, and different kinds of impacts?

That’s a great question. I cannot speak for everyone, but if you look at how we do it, we try as a foundation to inflict systems change. Systems change takes a long time, but the up-side is significant if you can achieve it. We do that by starting to understand a theory of change and understand our partners’ theory of change and try to look at what is the impact we want to achieve, what is the outcome we want to achieve through our investments, and then we work backwards and see what does it take to get there.

That means that we need to identify the barriers that are in the way of changing a system and break down into investments that we make and interventions that we make in order to get there. So, for us this is about building a very strong, robust framework on monitoring and evaluation around every investment we make so that we have good measureable key performance indicators for every investment we make so we can not only measure success but also learn from the failures we make. We take risks, so we will have failures as well as successes, but we need to learn from the failures.

One way we learn from our failures is also to spend quite a lot on evaluations every year. We take the most important interventions and programs that we have invested in, and we put strong third-party evaluation around that so that we and everyone else can learn from the mistakes we made and from the successes we had so everyone can build upon each others’ learnings. By doing it that way, we hope we can be more efficient in how we invest in the future but also how others can invest in the future and scale the programs that we cannot necessarily scale because at some points we don’t have the funds to scale any more. Then we will go and look for another challenge and another risk, and the scaling can happen with our partners.

I would like to touch a little bit on how you communicate about risk a little later on, but if I may, I want to turn to some of the approaches that C2G has been looking at.

Obviously, the absolute priority now is to cut emissions and drastically scale back CO2 emissions, but the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change made it pretty clear recently that the world will also need to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere in order to achieve net zero and eventually net negative and to keep warming under 1.5 °C with limited or no overshoot.

We have seen quite a lot of focus recently — this year in particular — on carbon-removal solutions both nature-based and technological. I was wondering if you have any thoughts on this and the debate that is getting increasingly active around the role carbon removal should be playing as part of climate action. How is IKEA Foundation thinking about these approaches, considering them? Do you see any risks that this could undermine efforts to cut emissions or create greenwashing, as some people would say?

Well, we are back to how do you introduce the subject. I think our first priority will always have to be to drastically reduce global greenhouse gas emissions, and that should be our number one focus.

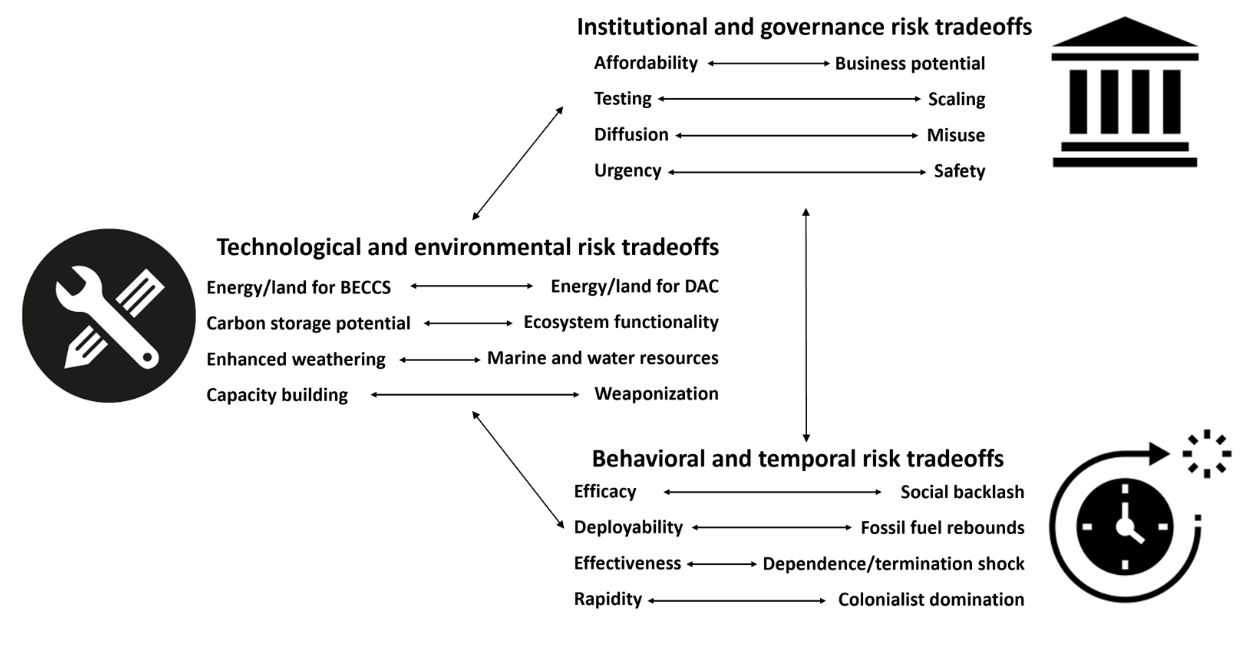

Having said that, there need to also be other tools that we probably have to reach out to in order to get to net zero by 2050, knowing that we also know that every option, including inaction, comes with certain risks.

We talk a lot about nature-based solutions. Planting more trees is of course one tool in the toolbox, but we also understand that planting trees is not about planting trees. It totally varies the kind of impact you can have depending on the geographic context and the natural conditions. So, it is one of many tools.

But I think we need to guard against the possibility of significant climate-altering technologies because it is very early days, and I think, instead of having that as an incentive to not do other things, we should motivate the governments, the businesses, and the societies to do more than we do today to actually reduce emissions before we talk about technologies like this. They could potentially help reduce the risks of some of the climate impacts, but they bring their own risks, as you know so well, their own costs and ethical concerns.

I think policymakers need to address this in a much broader sense. We need to have equity in the decision making. We need to have a governance structure. We need to have safety and accountability around this. Of course, that is why we support C2G because you are working with governments and with international organizations and civil society to actually build a governance structure around this so we know what we are doing, and if we do something we do it together instead of individually out of desperation.

Just to be clear, when you mentioned climate-altering technologies there, you were referring to solar radiation modification (SRM) as well as carbon-removal technologies.

We have direct carbon-removal technologies that we know work, but we don’t know how to make it work at scale, and it is still not at a cost level that we can accept; so we have to, as Bill Gates would say, “get the green premium down;” we have to find a way to commercialize these technologies.

I get very nervous. I will give you an example. A couple of years ago I was at the World Economic Forum, and we had a debate around climate change and different technologies. Some executive stood up and said: “Well, I don’t understand why this is a problem because emissions shouldn’t be a problem. We have technological solutions that could fix this.” That makes me very scared because that points toward people thinking, We don’t need to really cut carbon and do the hard stuff because we can use technology. That is really scary.

Turning to some of these other ideas that we are also looking at in C2G, there are some ideas that scientists have put forward, given the scale of the climate crisis and the shrinking window of opportunity, to help lower temperatures by reflecting a fraction of incoming sunlight, known as solar radiation modification or solar geoengineering.

You touched on the issue about governance before, and you are funding C2G’s work to catalyze the creation of international governance around SRM. Perhaps you could just expand a little bit on why you think that is so important and where you see the risks and opportunities for creating a governance space there.

As I said before, at this stage we have come so far in global warming that we need to look at every option to stop dangerous climate change; but, as you know, some options come with much higher risks and some options are less developed and we need careful consideration before we take those steps. Some options could have huge unintended consequences.

We cannot risk that we have unilateral action by one country to stop warming because it is getting at a very critical point for them because we cannot geographically limit the actions that they might be taking. When you think about the scenario described in Kim Stanley Robinson’s book The Ministry for the Future, when he describes one country saying, “Well, you might not like this, but we are at the point where people are dying because of the combination of heat and humidity, so we need to do something,” and they start doing something.

Of course this is science fiction, but it is also quite real in that it could happen that way because those responsible for most of the emissions — you and I living in our parts of the world — will be the last ones to suffer and those who have very little responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions today are the ones who will suffer first. We see that happening right now, and that is just going to get worse.

I think about solar geoengineering like I thought about artificial intelligence and social media 20 years ago. We knew it was coming, it came, and now it is extremely difficult to regulate. There is no way we are successful in regulating the Facebooks and the Googles of this world. Geoengineering could be even more challenging.

One of challenges of course is that it would have huge impacts for every country and every citizen on this planet, so one of the challenges is to make governance inclusive for as many people and groups as possible. What would the IKEA Foundation like to see in terms of broadening participation, including by young people, so a wider range of views and priorities are heard? How might the world go about that?

We are funding you to help policymakers make responsible and ethical choices in how to mitigate and adapt to climate change. We believe that this cannot be a process driven by scientists and experts. It has to be a process where everyone has ownership and every part of society contributes to this. We know that young people are the ones who are going to suffer the most from the impacts of climate change, so involving young people in creating their own future is super-important.

And we are not having effective global and properly democratic controls. The geopolitics of possible unilateral deployment of solar geoengineering would be very frightening and inequitable, so I think this has to come up on the stage and on the agenda as a much broader discussion, and not happening just among specialists and scientists but happening in broader society.

Think about a country like Chad, for example. It has 70 million people, 80 percent living below the poverty line. It is hugely impacted by climate changes right now. Lake Chad is drying up, and that gives all the fuel to their energy and to their nourishment. It is so important to them. Think about somebody coming in, a business coming in, a wealthy entrepreneur coming in, and saying: “We are ready to deploy a solar radiation mechanism and we are looking for a place to do it. If we deploy the technology over Chad, your weather patterns will change.”

It would be very tempting to do, but we don’t know about the unintended consequences. We need more insights and more knowledge before we can actually allow something like that to happen, but it could easily happen given that more and more countries and individuals will get desperate over the impact that they are facing day to day from climate change.

I wonder if I could ask a little bit about communications, something you are an expert in. It can be obviously quite challenging to communicate about climate change in a way that keeps people engaged and maintaining a sense of hope and agency but also accurately informed about the scale and complexity of the problem and how to balance those two elements. How does the IKEA Foundation approach this?

It’s challenging because when you work in philanthropy you experience on a daily basis this swing between hope and fear because you have insight into understanding how little time we have left. At the same time, you try to be optimistic. Every day we hear about poverty, we hear about climate change, about disasters, and about displacement, but at the same time every day we see how our passionate partners are working to change this. This gives us at least hope that we can drive some systemic change in this.

I think that is what it should be. We should focus on hope. We should not focus on doom and gloom. We should focus on all the opportunities that come with a shift away from the fossil fuel dependence that we have today. We are going to see better health, we are going to see a cleaner environment, we are going to see healthier food, and we are going to see increased job opportunities. Only communicating about the dangers of climate change could lead to despair, so I like to focus on the positive impacts that we will have as we go through this transition and change the way we actually deal with the climate change issue and the opportunities that come with it.

I hope you don’t mind, but I would just like to pick up on one of the issues you raised earlier, the nature of risk. I think communicating risk can be extremely challenging, how people can compare one risk against another risk. Have you had a sense of that being a particular challenge in your communications work, in how you communicate things? Do you feel that people inherently understand that there may be no risk-free pathways ahead so you have to find a balance between the two? How do we actually help people understand that it is measuring risks against each other?

That’s a complicated subject. Most people will not have the time, the possibility, or the interest in getting deep into this discussion, to really understand the different risks up against each other, and that is part of the reason we are happy that organizations like C2G are focusing on what they do and bringing a larger group of society into this discussion. People need to understand that there is a very different type of risk when you talk about limiting the number of miles you drive in a car every day, switching to an electric car, or thinking about how you personally use less hot water, compared to actually start thinking about geoengineering in the atmosphere. So I feel that communicating about risk is something that we have to do on different levels depending on who we are talking to.

The biggest risk that most people have not understood is how little time we have left to actually cut carbon emissions or greenhouse gas emissions by 50 percent in eight years and then get to net zero by 2050. I think very few people understand that eight years is a very, very short time and that we have to make enormous progress in the next eight years in order for us to stay somewhere close to the 1.5 °C target that was set by every country together in Paris in 2015.

We have been talking a bit about communicating with others, but maybe I will turn almost to a sense of communicating with ourselves or with yourself. It can be pretty tough working in climate change. I know that even the most hardened long-term scientists, experts, and professionals can sometimes think, Ugh, well, this is a big, difficult challenge ahead.

How do you personally keep a sense of hope and enthusiasm, while at the same time understanding that this is an extremely complex problem? What kind of philosophies do you turn to to help keep yourself going on this?

We can’t give up on the world, and if we stop focusing on doing whatever we can to limit greenhouse gas emissions and helping the world toward a net-zero world, we will just be giving up, and we can’t do that. I get very impressed, excited, engaged, and motivated by all the great partners we have that do good work in so many different arenas and in so many different situations to actually make the world understand better how we can not only fix this problem but fix it quicker.

I get also motivated by the fact that this is a level of responsibility that I feel for myself. I belong to the first generation that can actually feel the impact of climate change, and I am also part of the only generation that is the last generation that can do something about it, so we are at an inflection point in my generation.

I have to do whatever I can for my side, and it is a privilege to be running a foundation that has focused most of its initiative, energy, and financial resources toward fighting climate change. My responsibility is just to inflict the necessary change that can secure a livable planet for our children and our grandchildren, and I have no time to despair.