DiCaprio film heralds the era of carbon dioxide removal

A new documentary produced by Leonardo DiCaprio is putting front and centre one of the greatest – and yet so far relatively ignored – challenges we face as part of our collective efforts to tackle the climate crisis.

This challenge has been called different things by different people, including carbon dioxide removal, carbon drawdown, or negative emissions technologies. Regardless of the name, the challenge is the same. According to the IPCC, it is not sufficient simply to reduce our carbon emissions; we need to take excess carbon dioxide out of the air as well.

DiCaprio’s film – Ice on Fire (aired June 11 on HBO) – emphasizes the importance of an immediate, 2-pronged approach to the climate crisis, which includes both reducing emissions, and drawdown measures such as “direct air capture, sea farms, urban farms, biochar, marine snow, bionic leaves and others.”

It describes this drawdown as “perhaps the best hope for mitigating climate change.”

We at C2G are glad to see a well-known public voice addressing the need for carbon dioxide removal, which the IPCC made clear is now needed. It is an important message, and one we are raising with governments and other interlocutors around the world.

At the same time, we urge a healthy degree of caution.

The science behind carbon dioxide removal

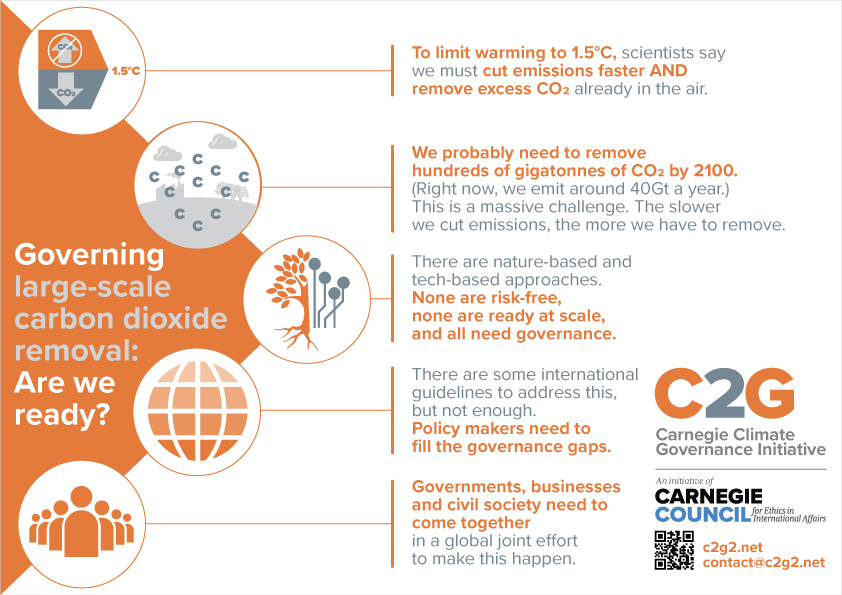

According to the IPCC, if we are to keep global warming under 1.5°C – beyond which the effects become increasingly damaging for communities and ecosystems around the world – we would need to remove on the order of 100–1000 gigatonnes of CO2 over the 21st century.

The upper range of this estimate – which many scientists believe to be more likely – is 20-25 times the size of our current annual emissions.

Tackling this reality marks the next phase of climate response. This is a massive and complicated undertaking, and one which policy makers around the world are only just waking up to.

Removing CO2 is much more difficult than putting it in the atmosphere in the first place. It is expected to be very costly, and raises many profound governance issues. And the longer it takes us to reduce CO2 emissions, the more difficult the removal challenge becomes.

Given its limitations, CDR will likely take decades, if not longer, to have a discernible impact on the climate system. It will also take decades to scale up those approaches society deems acceptable.

Time is a luxury we may not have. At present rates of emissions, warming in excess of 1.5°C will occur between 2030 and 2052 (IPCC 2018).

Governing risks around carbon dioxide removal

All approaches to carbon dioxide removal – whether nature-based or technological in nature – also bring with them a complex mix of risks and costs as well as potential benefits.

It may be that some of the ideas currently being proposed turn out to be unfeasible at the necessary scale. Certainly none of them will be easy, and all would need to be governed – both nationally and internationally.

Take, for example, the issue of large-scale afforestation, which is the proposal to plant billions more trees to suck excess carbon out of the air.

While it’s hard to argue against trees, where is the land to come from, with two or even three billion more people expected to inhabit our planet by century’s end?

Whose land would be used? Would that affect agricultural production and hurt food security? How should the rights of current inhabitants of these lands be protected, and by whom?

Decision makers need to take a holistic approach to suggested approaches to large-scale carbon dioxide removal and assess the impact of action at this enormous scale against a whole range of sustainable development outcomes, including biodiversity.

In 2015, the world committed to the Sustainable Development Goals, as well as the Paris Agreement. We cannot attain the latter at the expense of the former.

Financing the business of carbon dioxide removal

The role of business and finance will also need to be looked at closely.

What market incentives will be needed for the private sector to get involved? How do we ensure carbon dioxide removal results in a lowering of overall carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere – which is, after all, the ultimate goal – and does not become an excuse for ‘business as usual’ by fossil fuel companies and the governments they lobby?

What public funds should be used, and from which sources? Without a price on carbon, who will pay for the research and deployment of these emerging approaches, including in developing countries? How will the public be protected if there are mishaps or leaks? Who is accountable and how will liability be assessed? How will the effects be accurately monitored, evaluated and measured?

There are hundreds of questions like these, and policy makers have not yet begun to engage with them with the alacrity that the science suggests they should.

That’s why the governance conversation needs to start now at all levels – international, national and sub-national. Effective governance can help address these knotty issues and play both a regulatory role, as well as a facilitative role. Both are needed.

Filling in the governance gaps

A recent C2G report Governing Large-Scale Carbon Dioxide Removal: Are We Ready? takes a close look at what governance currently exists within the UNFCCC.

It shows that while carbon dioxide removal is not a new issue for the UNFCCC, crucial governance gaps remain at the massive scales now being considered. If the world is to successfully take on the carbon dioxide removal challenge, these gaps will need to be filled.

Creating effective governance can be every bit as challenging as designing new technologies in the first place.

We believe now is the moment when governments, businesses and civil society should come together to figure out what it would take to remove carbon dioxide at the levels the science demands – and how that should be governed.

Having these key actors in the same room, joining in a common discussion, is essential for addressing how the world will respond to the carbon removal challenge in a way that is seen as fair, inclusive and durable.

Given the scale of the challenge, and a quickly closing window of opportunity to do it, there is no time left to lose.

A nigh-impossible question, indeed. If we are to think creatively, really outside of the box, then the entire world must pivot our cultures & priorities to adopt lifestyles like the indigenous Amazonians, who, over 5,000 years, cultivated the world’s largest manmade food forest in the Amazon Rainforest. Living beside and among wild and diverse life, global adoption of a hunter-gather lifestyle, the world’s economy no longer based on industrial production or conventional growth models, and instead wellbeing defined as community, physical exercise in nature and the outdoors, and a global food forest society as the painting of the next chapter of human civilization are fundamental to our so-called transition. Personally I am excited for this future, a life in close harmony with ecology, whose denial by industrial civilization has been at the root of most injustice for centuries. Let’s do it, current vested interests be damned! They’re going to vanish with ecological collapse anyway so now is the time to build our new tomorrow.