C2GTalk: An interview with Amy Luers, Global director for sustainability science at Microsoft Corporation

How can companies ensure carbon dioxide removal has a positive impact?

13 March 2023

Is the private sector taking genuine action to tackle climate change?

How does Microsoft approach carbon dioxide removal?

How can companies assess the quality of nature-based carbon dioxide removal?

What role can new technologies play in carbon dioxide removal?

What role might solar radiation modification play in tackling climate risks?

New thinking is needed to ensure high quality nature-based carbon dioxide removal offers genuine and long-lasting benefits to the climate and biodiversity, said Amy Luers, Global Director for Sustainability Science at Microsoft Corporation during a C2GTalk.

Large-scale removal through CDR technologies lies further ahead, although most of the basic technologies already likely exist. While Ms Luers is not in favor of pursuing solar radiation modification, “I am very much in favor of enhancing our understanding of the risks and opportunities it presents, the governance challenges, and how decisions are made around this.”

Amy Luers is the global director for sustainability science at Microsoft Corporation. Previously, she served as executive director of Future Earth, assistant director for climate resilience and information at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) in the Obama administration, director of climate at the Skoll Global Threats Fund, and senior environment manager at Google. Dr. Luers spent the first decade of her career working in Latin America, where she cofounded Agua Para La Vida, a nonprofit organization that works with rural communities to enhance access to potable water. Currently, she serves on the foresight committee of the Veolia Institute, and on the boards of several organizations including the Carnegie Climate Governance Initiative and the Global Council for Science and the Environment. Dr. Luers is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations and has served on committees of the United States Global Change Research Program and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. She has both a PhD in environmental science and MA in international policy studies from Stanford University, and a BS/MS in environmental systems engineering from Humbold State University, and BA in philosophy from Middlebury College.

Below are edited highlights from the full C2GTalk interview shown in the video above. Some answers have been edited for brevity and clarity.

What does the Global Lead for Sustainability Science at Microsoft do?

Our team helps the company with its mission on sustainability across the board. It has three buckets of areas of work. The first is to support our company’s operations. We have big commitments, as you said, to be carbon negative, water positive, and land positive — to protect more land than we use — and zero waste by 2030.

To do that we want to be directed by science, making sure our strategies are guided by science, but we also have a sustainability industry where we help companies go on the road that we are going on and partners around the world. In that context as well we want to make sure we are developing the tools and working with customers to bring science and technology together to these solutions.

Finally the third area is creating enabling conditions, whether it be policy, advancing science issues, advancing new technologies in the space that is beyond Microsoft, and standard setting as well, working with the community outside of Microsoft to make sure that the enabling conditions for Microsoft to achieve and all of our customers to achieve is a critical one to our team’s work as well.

Great. Let’s talk a little bit about the context. It has been a tricky few months for international climate cooperation. The recent UN climate summit in Egypt underlined a great sense of injustice in developing countries that they are suffering the costs of a crisis they did not cause which is harming their development objectives.

At the same time there was some progress on loss and damage, but there was not much progress on mitigation and cutting and ending fossil fuel emissions. I just wonder what your thoughts are on what more could be done to ensure both climate goals and development goals are essentially working hand in hand in a way that is equitable and fair.

I think this in many ways has been the question throughout the whole equity issue that I see as the central theme of the climate struggle from the beginning, these inequities in the world of who has been predominantly responsible and who is most vulnerable. This is not a new topic, but it is reemerging in the discussion with greater intensity as we are experiencing the impacts of climate change much more intensely in recent years.

It is sort of inevitable that it would reemerge in such a dramatic way in many ways. This was actually the root of my dissertation years back and was my motivation to come into the space of thinking about how we deal at a global level with these issues. There is certainly no simple answer, but I think the key direction that we need to head in and that we are beginning to head in is just the recognition that issues of equity and social justice are not separate from the core challenges of climate and have to be integrated into every part, not attached on afterward, not a separate stream, but core to this. So we need mitigation, we need adaptation, we need to think about loss and damage issues, and all of those are embedded into it. We have to think about equity issues.

We do this at Microsoft. At Microsoft we do have a social equity justice program within our core sustainability work, but part of that person’s role, just like my role, is to look at science across all of those. My team’s role is to look at science across all of our programs. Our environmental justice program is to look at science and social justice all of these programs to make sure it is embedded into our investments in the Climate Innovation Fund, make sure it is invested in our policy work, make sure it is invested in our business work, and our purchasing of renewables. We have this lens that is embedded throughout.

One of the many things that I love about working at Microsoft is that it actually is one of the core values when we do our reporting too. We are asked that question: How are we addressing these issues? I think embedding it at that depth is important. It has taken a while. I feel we have come a long way on that relative to how we used to think about this 20 years ago when we were starting to address the climate issue.

We certainly hear a lot more amongst climate experts and to a certain degree policymakers on these issues. At the same time, a lot of countries in the Global North are facing increasing financial pressures. Are you still seeing the actual level of practical support or the development of a willingness of people in the Global North at a time of financial pressures to help support essentially developing countries do the transition that they need to deal with the consequences, loss and damage, and adapt to the changing climate, which after all came from primarily activities in the Global North? Are you actually seeing this justice talk put into real action at a time of financial pressures, or is it something that might only be done in a less financially pressed time?

Of course the financial situation globally is challenging for every aspect of society. I don’t think it has put the brakes, as one might have thought, on the climate space and the sustainability world as one might fear, maybe a slowing down and thinking about different things in different areas, but I think it is still front and center of the business community’s world. It certainly is front and center at Microsoft. I think one of the challenges is integrating equity issues across policies and recognizing that global cooperation means that we need to address the issues of adaptation and loss and damage together with mitigation. It is critical.

One of the challenges for operationalizing that is, as I see it, the challenge of quantifying and putting metrics to adaptation and loss and damage and distinguishing that from development aid. I think that has slowed down the challenges of investment in adaptation both from things like the World Bank and the U.S. Agency for International Development but also philanthropy and private sector. It has constrained our ability to integrate this in an effective way, and I think it constrains the ability to think productively about how even to address loss and damage because there is this spectrum of what is development aid and what is actually this contribution for climate loss and damage?

The science has made incredible advances in our ability to attribute the climate event, the weather event, to the percent that climate change has addressed it, but that is not the same as attributing the impact. The impact also has to do with our vulnerability. It has to do with what were the decisions about where we developed and how much more likely would that have been versus because of our lack of development, so the ability to actually attribute the loss and damage per se to a certain event versus another and even the adaptation unit makes integrating it into policy and investment strategies very difficult.

I think that science and technology and functionality complicates what also has this political and economic side to it. I don’t think that solving the technology issue will all of a sudden make all of the other problems go away, but I think it would help to advance, to clarify how we do that, because if you don’t clarify that, then the issue of loss and damage because open-ended. There are no bounds to it. So it is hard for some of the wealthier countries to come in and say, “Yes, we are open to taking liability for everything.”

I think advancing in that space is important for us all to think about, and I know there is a lot of work being done in that space. It is hard because part of it is science, part of it is art, and part of it is politics.

Are you putting together some thoughts personally on this as to how you would actually go about disentangling these different elements?

It is something that I have been passionate about throughout my career, how you think about doing these things. Initially it was to figure out how do you assess someone’s vulnerability and how do you assess decreases in that vulnerability in terms of are your investments being effective. It is something I engage in whenever I get an opportunity to bring people in because I think it is so important and central to this global issue, but at this point now it is not central to my work.

At Microsoft we are also thinking about how do we support the world in adaptation space. In that sense I do think there is a role for science and technology at that intersection to do it. Maybe watch that space, and I will come back to it at a different time.

Fantastic. You keep on talking about technology and at a time of complicated international relations that has been a relatively positive story. We see climate tech booming perhaps more than other forms of tech and innovation all over the place. The price of clean energy continues to fall. Business leaders also increasingly acknowledge their part in tackling this criss.

At the same time we also see growing scrutiny of the private sector’s commitment to climate action, questions of whether what they are doing is real, whether it is greenwashing, and so forth. Perhaps before going maybe into more detail about Microsoft’s own commitments, where do you see the state of the private sector — I know that is a very big concept, the “private sector” — business leaders’ attitude to climate? Are we actually seeing a genuine shift taking place right now?

I think across the board the private sector is deeply engaged on this issue. It is moving beyond what I think was initially a reputation issue. You had to at least have something which was promoting this greenwashing. I think it is also a survival issue for companies both because there is a recognition that companies need to address this internally because of the risks that are coming on — transition and physical risks. This is a world that everybody needs to adjust to.

Also there is a sustainability service industry that is emerging and competition in this space. If a company’s direction does not have some component of meeting those needs to society as well — not all companies of course, but it is pretty across the board, not just mitigation but managing climate risks — and putting that also in addressing, conserving, and being nature-positive as well. That part of it — how do you play in this space, how do you protect your business in the context of the business model, the business infrastructure — is I think a critical piece.

You mentioned the challenges of how do you know that this is not just greenwashing. I do think there is a need to have a lot of transparency, and increasingly there is that demand for transparency, standards, and compliance, and those are things that we call for. We need to step up on that, and I think part of the science and technology is enabling us to as well. When I think about this and look out five years, I think how we are reporting and how we are verifying is going to change. It is going to look different than it does today, and keeping up with that alone can be a fulltime job because it is changing so quickly. I think that will help facilitate faster movement.

It would certainly be in the company’s interest — which is genuinely doing good stuff, as it were, for the planet — to have mechanisms out there which allow for scrutiny to show that their stuff is real whereas other people’s might not be. Are you seeing governments sufficiently listening to your calls for having these clearer verification standards, monitoring standards, and all the kinds of things that might help convince the public that this stuff is real?

In some ways the private sector has been ahead of governments on this kind of stuff. How are you seeing the response by governments to creating these tools to address the greenwashing issues. For many nongovernmental organizations right now this is the year of challenging greenwashing. It is the thing they are on. How are you seeing the ecosystem responding to that challenge?

I think at the Conference of the Parties 26 (COP 26) the UN secretary-general launched an initiative to take on the private sector in a way that the United Nations hadn’t before. Obviously there had been a real opening of the tent to other actors over the last five to ten years in the United Nations, so not that that engagement hasn’t been around, but the call for an expert panel to structure guidance for private sector and other nonstate actors to make commitments in this space and hold them accountable for that in a way that they haven’t I think is an indicator of where we are headed. The European Union, the United States, and others are beginning to set compliance for reporting and disclosure, so there is movement in that space.

In terms of the technologies I think that is almost coming from the private sector. There was an interesting report out recently — I guess it came out in September — from the National Academy of Sciences that brought engagement globally of trying to make sense of all of the different sources of greenhouse gas information for decision making, verification, and disclosure processes that the government process is going into, and I think one of the key messages in that is that the direction the future is headed in and that we need to accelerate in order for us to be able to have reliable and verifiable information for greenhouse gas reporting is in this hybrid mode where we combine activity data, we combine atmospheric data, we combine modeling and artificial intelligence, and we do this in a way that is transparent enough that can be verified.

We have projects coming out in this space. There is some evaluation of saying: “Well, this may be directionally in the right way. We don’t have enough information to evaluate it yet, but that’s the direction that we are heading in.” I think working that whole space out, where we land on that, will take some time and will take public-private partnerships. There is a big role for the private sector in that space for sure. I think the combination of public and private sector partnerships in the science and technology space combined with the government’s role in setting the compliance mechanisms and review processes is what needs to come together to get us to move forward.

Maybe I could now dig a little bit into Microsoft’s amazing, striking promise a couple of years back to become “carbon negative” by 2030. That means both cutting emissions at different scopes — I remember Microsoft had an interesting blog laying out some of those challenges and reports since — but also removing as it were historic emissions, removing carbon from the atmosphere. Two years on or so, what have you learned about the opportunities and challenges for carbon removal? The sector certainly seems to be growing pretty quickly. Where do you think we stand right now on the carbon removal side of things?

We engage in carbon removal on multiple different fronts. We have a Global Climate Innovation Fund, a $1 billion fund. Not all of it, but a lot of that goes into investing in carbon removal and reductions. Not exclusively, but a lot of that is in technology base, direct air capture and storage (DACS). We have invested in Climeworks and their new plant in Iceland. We also focus on this in the context of we have a program that purchases its removal, as you know, and we also engage in this in the context of our policy work. I will say we are also innovating in our own industry setting to figure out how, within our structures at different sites, we can remove carbon in the same sector.

“Insetting” as opposed to “offsetting” I think is the term.

Insetting, yes. We have an incredible cutting-edge research institution, Microsoft Research. My team works with them to connect with sustainability sciences around the world, so we are engaged on these issues. It is an exciting space to be able to think about these because we need to think about these from so many different angles to address them.

The technology space needs that investment in all that space. It is early stages. We continue to push forward in advancing on all these angles, but on our personal purchases right now in terms of carbon removal the vast majority of them are in nature base, and that is basically because of the combination of price and supply. That will be true for awhile because ramping up of the supply of technology-based removal is still years down the road.

In the contest of nature-based removal the challenge is that there is a limited supply of high-quality removal. Part of the challenge is that it is hard to find the good supply because we don’t have the structure to weed through it. We have a growing team of people who are working fulltime to try to sort out what is the best quality. I am incredibly impressed by the rigor that our team works at.

Actually I would love for you to say a little bit more about how you go about assessing the quality. Since we are on nature base, let’s take on nature base and move to technology in a second. On the nature-based stuff, especially as there has been more and more scrutiny and in many cases rejections of nature-based offsets as junk, there are at the same time definitely efforts both voluntary and through different policies in the European Union and so forth to try to start working out what are high-integrity as opposed to low-integrity removals.

I can imagine as a company you have your internal science but also a bewildering array of ways to measure this stuff. What standards are you using to decide in effect the “good” carbon removal versus the “bad” carbon removal, or however we might say it simplistically? I would love to hear more about that.

When we get a lot of proposals in actually the first lens is that most of the carbon in nature supply out there is avoided emissions offsets and not carbon removal. Even within that one lens, we have constrained our purchases to carbon removal. To do that in the first lens is actually sometimes difficult in itself because people present it — even though we ask for removal in this joint context and they make the case that part of it is removal, then you have to assess which one is removal, so there is that component.

Of course some of the big issues there are questions of permanence, leakage, and additionality. These are the big items there. We are increasingly — and I certainly am a big believer in this — needing to recognize that you cannot rely on investing in nature as permanent. When we think of our investments we have a certain percentage that is reliable permanent, reliable medium, and potentially more shorter term with an understanding that we will be shifting to a bigger percentage of that reliable permanent as supply increases and a recognition that we need to deal with the reality that temporary storage — for example in forests — is more temporary, and how do we deal with that?

Part of that is we have buffer zones. Part of that is we are beginning to innovate and think, Well, maybe we should be thinking about this in a more broadly different way and just really face up to this. We still figuring that out. My team has done research with modelers around the world to think about how to think about this in a planetary context with climate modeling.

One of the things we have been looking at is modeling the value of temporary storage with it, not in the context of comparing it to permanent, which a lot of people have done where that has been the sort of focus, but instead in terms of comparing it to peak warming. One analysis we did is that if we store carbon in forests for let’s say 30 years and we are able to reach peak warming by then. Then everything is gradually lost. There is still a value for cutting off the peak. So there is a permanent climate value as it is not seen as replacing carbon emissions and reductions of fossil fuels but seen as complementary. That approach to recognizing the value of nature for trimming off that peak and not seeing it as equivalent to permanency but seeing it as being critical for permanent climate impact as a complement to emissions reduction I think is a critical space. Unpacking how to integrate that into our policies is critical.

I want to say one other thing about that because we are also looking at this: How do we integrate this in the context of thinking about it together with biodiversity? Nature has to be part of the solution for climate. It provides carbon removal. There is carbon storage there. It is critical for resilience, and if we don’t think about this holistically and we don’t think of it as a core part of the solution, we will be in trouble across the board.

I fear that these questions about the challenges of investing in nature for climate solutions being a greenwashing could push us away from investing in nature, which is a bad road to go down. I am working with our team and researchers around the world to say: “Let’s figure out a way that characterizes nature’s contributions to climate solutions effectively rather than try to put it in a box and have it meet standards that it can never meet.”

That sounds very sensible. I guess the question is, though, how do you then put that into an equation that says, “Microsoft is now net-negative,” when maybe temporary is only going to be there for 30 years or whatever? That is probably simplistic, saying, “Are we plus or minus now on the carbon ledger?” You have a claim, “We are going to go net-negative,” and yet some of this stuff is tied up in nonpermanent forms of carbon removal. How do you actually go about accounting for that against that claim?

As I said, we are working with people internally and externally and thinking about this in this broader context, but from my team’s perspective in thinking about the science of it if you think about the cumulative role of ten years for a temporary piece and think first there is a critical urgent need to protect nature now. If you want to think about that in the longer term, what is a temporary timeframe within which to think about that? It is not a year. One hundred years — I think it is more than that — is for the permanent, but if you think about this in the context of peak warming, because that connects the short term with emissions reduction. If we get to peak warming, that means that we have effectively reduced our fossil fuel emissions as well.

Then in the context of giving that credit you can be accounted for in terms of the cumulative pieces, but you don’t have to contract for a thousand years, which is unrealistic except for something like DACS. You can think about it as a short-term and long-term piece. Then, if you want that equivalency long term, you need to have that short-term piece repeated, this sort of stacking on top of each other but within this context of a short-term window. It is not a year because a year isn’t going to help you, but if you think about it, 30 years with the assumption that we are in a position to be able to also reduce the fossil fuel emissions, then we have a win.

The other piece of it I think to do that is that right now we have this structure that is very binary. We say: “We have these constraints. You have to be permanent, you have to be additional, and you have to have no leakage.” Because it is either yes or no, it actually pushes everybody right to the line where you could say, “Okay, we have to choose yes or no, so we are going to choose yes.”

The way I think about it is that we need to move beyond the binary approach to our crediting, and as we do that we will be able to get a broader spectrum of the value and look at the likelihood that we are going to achieve these and create the buffer zones so that we can at least get those important chunks to capture the value of the short-term piece. It is not simple, but I think we need to rethink how we are doing this and not just tweak it and try to fit the square peg into the round hole.

If we could quickly turn to the technological approaches to carbon removal. You have mentioned DACS, direct air capture and storage, and your investment in Climeworks, which certainly has had a lot of attention recently. There are obviously a lot of other approaches as well. There is a hybrid approach — bioenergy capture and storage, and all sorts of other ideas around soil regeneration, biochar, enhanced weathering, and all the rest of it. Some of this has had a bit of a boost recently by the U.S.’s Inflation Reduction Act, which definitely envisages backing for these technologies.

Then again, you said you don’t actually see this coming online in a significant way for a little while. I would love your thoughts about the state of these new technologies. How long do you think it will be before we actually start to see large-scale opportunities there to remove carbon? I would also be fascinated to learn a little bit more about what your team is dreaming up. Have you got any new approaches that we haven’t already got on our various carbon removal fact sheets, insetting? This is it, right? Companies are trying to work out how to do this in a way that is complementary to their existing operations and how they use what they know about how to make something. Can you give me a sense of where you see the technology sides of carbon removal at the moment?

I first want to highlight that we are not going to remove our way out of this problem. I want to highlight that it has got to come onboard at scale for us to succeed by midcentury, but it only makes a dent in the problem if we basically reduce to almost 90 percent of our emissions more broadly at a global scale. I do want to emphasize that.

We put a lot of attention to carbon removal because we made a commitment to remove all of the emissions that we have put into the atmosphere since our company began. That is one of the reasons, but we also realize that there is a role at the intersection of science and technology that the world needs to succeed, and so we are focused on that as enabling conditions that we have set. I want to emphasize that.

In the context of the technology space my sense is — and I think broadly many people at Microsoft believe this too; I don’t want to speak for the company as a broad-brush statement, but I do think a lot of the leaders in this space believe this — that the basic technology that is going to succeed in this space in carbon removal probably already exists. It is just about refining it. I am not saying there won’t be breakthroughs, but I think that whatever is done at scale by midcentury there probably is a version of it on the market today.

Having said that, I mentioned that we have Microsoft Research, which has a sustainability research program. My team works closely with them to set the agenda, make connections, and work in this. One of the big areas is carbon removal, and a key piece of that is materials. Artificial intelligence (AI) research can do wonders to accelerate research findings in materials. The analogy I think about is how AI has been so helpful in accelerating the discovery of vaccines for Covid-19. That ability to accelerate and explore new dimensions of opportunities that we could not do without AI is exciting, but you need to also work with people who are also working on the ground to have that feedback. That is one of the things that has emerged from our Microsoft Climate Research Initiative that we launched last year and is beginning to expand, working with people around the globe to leverage Microsoft’s leadership in the AI space with people who we are working with.

I do think that is an area where there are some of the bottlenecks for the existing technologies. Materials is a huge piece not just for carbon removal but also for so much of the embodied emissions challenges that we have in our supply chain in addressing these issues. We are investing quite a bit into the materials research space.

Then operationally how to integrate the components of this into infrastructure, so it is not necessarily only in Iceland, but how do you have this be more operational? I don’t think this is the core technology is my sense, although I think there are advances in biochar and weathering, but the core structure, my instinct is that those will be there.

It is an exciting field. In the meantime, right now the temperature continues to go up, CO2 emissions continue to go up, and climate impacts continue to intensify. Given these risks we are seeing some scientists exploring the potential for solar radiation modification (SRM), the idea that you could reflect a small portion of incoming sunlight back into space. Of course these ideas bring risks and uncertainties of their own. The challenge now is to work out whether that could be an option to reduce risks and how you actually go about measuring that against all sorts of different metrics and outcomes.

What are your top-line thoughts on solar radiation modification and that whole area of inquiry?

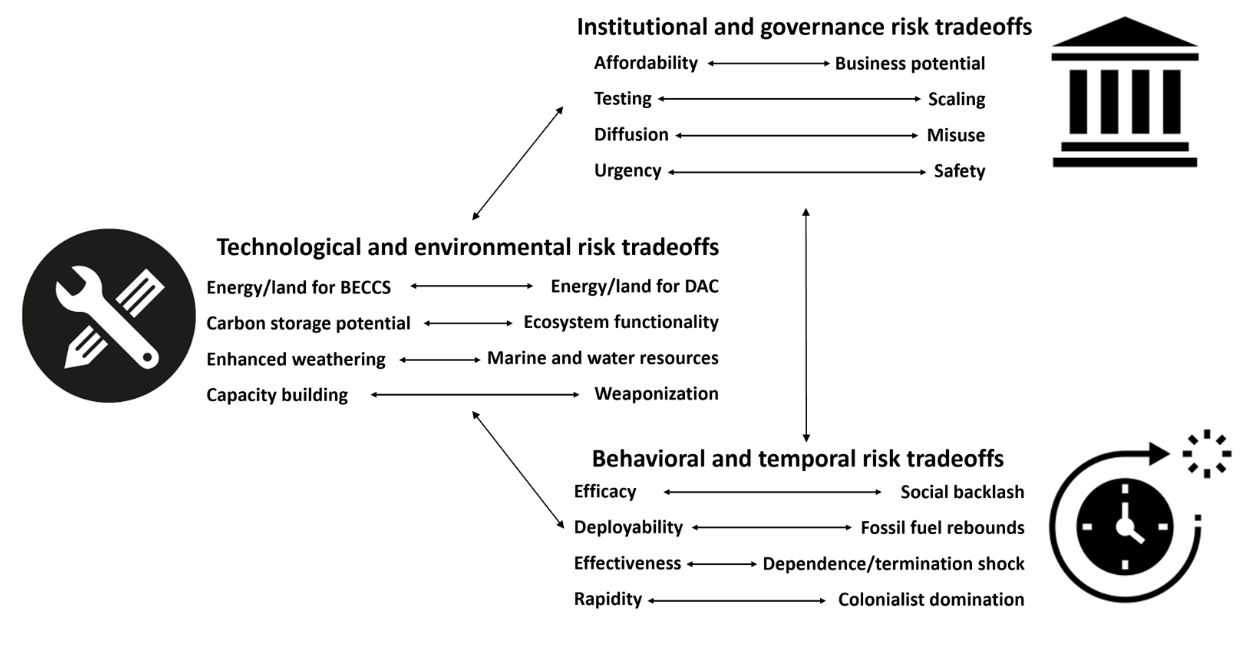

As a simple answer, I am definitely not in favor of pursuing SRM. Having said that, I am very much in favor of enhancing our understanding of the risks and opportunities it presents, the governance challenges, and how decisions are made around this. I think it is essential, and I have thought so and been engaged with C2G but even previously in trying to push how we think about these issues and more broadly setting up the structure so that we can ensure that we can do the science safely and recognize that this has to be part of a spectrum of challenges.

The solution set that we are exploring — that is not the solution set that we will necessarily choose — has evolved over the years. It used to be mitigation big and adaptation as a footnote. Mitigation and adaptation then came together, mitigation expanded to carbon removal. That was seen as an outside, crazy thing for so many years. Now it is mainstream. Then loss and damages emerged. I think the issue of solar radiation management and others in this general realm have to be part of the discussion alongside all of these. Having said that, if I was asked, “Should we do this?” I would say no, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t have the discussion.

What kind of research do you think might be needed, and what would be a good way to fund and govern that research?

I am definitely not in a position of knowledge in depth to be able to present a research agenda for SRM by any stretch of the imagination. I think one of the key pieces of this is the need to start to have a discussion about what the world looks like if we don’t meet 1.5°C and 2.0°C. I think we can’t give up hope and we can’t stop working toward that. No one can stay working in this field for 25 years and not be optimistic because it would have fizzled out a long time ago, but I do think we need broader science and policy discussions of what happens.

That is not just about the impacts expected but how would and should we respond. This would include SRM, loss and damage, managing mass-scale migration, and large-scale climate tipping points. These are all interconnected. I would argue that part of thinking about the agenda and research funding in that space is about how do we integrate this next phase.

There is a special report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) on 1.5°C that was done. How can we position these sorts of questions of special reports that are maybe not squarely in the IPCC’s realm but broader without undermining efforts to keep moving to the 1.5°C realm? I think we can do it without undermining it because, to be honest, it is so scary once we outline it that it is going to reinforce the need, but I still think that is a conversation we have to have. I do not think that SRM can be thought of outside of those other pieces. That is where I stand on that.

To be honest, there was a lot of reluctance for a while to acknowledge that we are likely to blow past 1.5°C for some reasons, but over the past year people have crossed that, and basically more and more reports — the United Nations, leading scientists, and in the media as well — “Let’s just deal with the reality.” Now of course you have this Global Commission on Governing Risks from Climate Overshoot to try to deal with reality, the almost certainty that we will blow past 1.5°C.

To begin with the ones with the most to gain or the most to lose from getting this right is the Global South. How can the Global South be better included in these conversations around SRM and the other things? What more can be done to support and include the Global South in this conversation?

I think as we begin to expand that discussion on how do we manage a world past 1.5°C and even past 2.0°C and begin to look at what is that outer bound because even the models we have — it is super-exciting to think about the ambition. Sure, we need more ambition. We always need more ambition, but the reality is that if we direct our energy to motivating more ambition, we should direct that energy to just implementation now it seems because we are pretty good on the ambition.

Still, the models that say where we are headed are only true if people are able to implement their ambition. So that is a challenge. There is still uncertainty in that. I know that some of the higher scenarios in the IPCC are now, “We shouldn’t even be using those because they are unrealistic,” and that is a super-exciting discussion to be having.

Having said that, I think that as we begin to look at that world of post-1.5°C and 2.0°C these issues that are emerging around equity are going to become even more front and center. I think that discussion and that agenda has to have equity at the middle or we are not going to be able to achieve all of those different pieces and we will at some point have scenarios that go high again because that has to be the central piece.

How does that happen in general? It is interesting. As you mentioned in my introduction I was the Executive Director of Future Earth, which is an international network of researchers and innovators to support policy and action on sustainability. I remember when I was asked to be executive director I said: “You don’t want me. You don’t want someone from the United States leading this organization because it has to be driven by someone in the Global South.” I did take on the role for a few years, but I think that the reality is that we need to have the voice at the center.

Future Earth has expanded its presence now in the Global South, adding offices in different areas, with a hub in India, one in Africa now, and expansion in Asia. I think that sort of central understanding of what are the issues in those areas as we move into this world of thinking about what happens next will be critical for that structure moving forward, not just in the IPCC and Future Earth kind of world but at that intersection of how do we work in the science and technology and policy business. We need to change the center of gravity so that we can be grounded in that perspective.

That is skirting the question a bit, I realize, but I think that is a fundamental mindset of how we think about this. It is hard to do, but I think it is a mindset change.

I realize we have already gone over the time we have, but one last thing. You mentioned you are optimistic. You have managed to maintain an element of optimism. How? Right now I am listening to the Greta Thunberg compilation of all the science on Audible, and my goodness, it is grim listening. How do you actually maintain a sense of optimism and motivation? Do you turn to any philosophies to help you do that, any particular practices? What do you do?

Three things I think keep me optimistic. You mentioned Greta Thunberg. I think youth — I am thinking about my kid, who is 20 now — for the last five years they have been very involved in climate activism and have shifted to seeing social justice as this intersection and are leading the way. The depth and passion of the transformation that they see and their cohort sees and that we see around the world — but that personal connection also I see with my kid — is I think inspiring. I was an activist when I was young, but the depth of understanding of these complex issues by youth gives me hope. It also motivates me because they are our children.

The other area where I see inspiration is actually in the science and technology realm. For so long so much of the science was running these different models and saying: “Oh, my gosh, what do we have to do on policy? We’re heading to 6°C if we don’t do anything.” It is scary, but I think especially being here in a place like Microsoft where this intersection of the incredible innovation in the technology space with the sustainability science, what you can do, how you can think outside the box and be able to imagine changes, totally revolutionizing how business models work and how we do things is I think exciting. Of course there is a lot of context outside of that science and technology to make that happen fast enough, but I think that is there.

Another area I think is the business world. I do think that the private sector has a huge role to play if we are going to be successful in this. I am not saying there are not challenges with that, but I do think that there is a role that as we rethink our business models and as we, as Microsoft, through integrating the digital transformation help others rethink their business models we can make this happen.